Fifteen years after the Escondido Police Department first experimented with body-worn cameras, and 10 years after protests in Ferguson, Missouri, sparked national interest, the technology has become vital to modern-day law enforcement operations.

Since the time of Ferguson, when Michael Brown was shot and killed in an altercation with police, ongoing debate about law enforcement transparency has led to the rapid expansion of body-worn cameras used by police and sheriff’s departments. That increased use has brought unanticipated challenges — determining which videos should be reviewed immediately, and figuring out how best to securely store millions of clips at increasing cost.

Add to that a new challenge — a controversial artificial intelligence program being used to review the mountains of video and audio.

The first body-worn camera usage by San Diego County law enforcement came before Ferguson in 2009.

“I had bought a little tiny micro action camera that was designed for people to throw on their mountain bike or to film a bungee jump,” Escondido Police Department Lt. Craig Miller recalled.

The $60 camera impressed his captain, so the department began testing half a dozen of them.

“Within about three or four weeks, we captured an officer-involved shooting on video, and the department was sold,” Miller said.

Today, every policing agency in San Diego County uses body-worn cameras except for the California Highway Patrol. The CHP finished testing them in Stockton and Oakland and has gotten the funding needed to roll them out statewide in 2025.

Today, every policing agency in San Diego County uses body-worn cameras except for the California Highway Patrol. The CHP finished testing them in Stockton and Oakland and has gotten the funding needed to roll them out statewide in 2025.

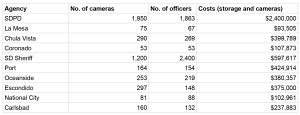

Currently in San Diego County, there are 5,305 law enforcement officers using 4,152 body-worn cameras, costing in excess of $5 million a year. The largest number of cameras — 1,863 — are owned by the San Diego Police Department.

Department spokesman Lt. Daniel Meyer summed up the current view of most law enforcement, which has come to embrace the cameras.

“Transparency is key to the success of modern-day policing and BWC’s are one of many very important tools in that pursuit,” Meyer said. “BWCs hold the public and law enforcement accountable.”

He added that the cameras are “vital to modern-day police operations.”

Research on the impact of body-worn cameras has grown rapidly, and an April 2023 analysis of 30 studies by different law enforcement agencies found “statistically significant reductions in use of force” in 14 studies, and overall, “the current body of research suggests that police BWCs can lead to reductions in use of force by police.”

Janne Gaub, a criminology professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and a contributor to the analysis, was part of a research team that studied citizen and officer perceptions and use-of-force complaints in Tempe, Arizona, and Spokane, Washington.

Gaub noted that, at first, “line-level officers were very skeptical of how the camera footage was going to be used by their superiors in terms of, are they just going to go on a fishing expedition, trying to find things we’re doing wrong?”

“A number of unions fought tooth and nail to try to prevent the rollout of cameras,” Arizona State University criminology professor Michael White said. “Is my supervisor going to be watching all my footage and trying to find these little incidents where I can get jammed up?”

That fear has largely vanished, Gaub said.

“As long as there’s not a significant cultural clash there, where they just are very, very skeptical of each other, then officers eventually come around to viewing them as a positive,” she said.

Further research showed that a local department’s culture “really makes a huge difference in body cameras’ impact, ranging from the decision to implement, how it’s implemented, the outcomes that that department will experience,” Gaub said. “We saw this a lot with use of force, where some departments saw dramatic declines and use of force; some moderate declines in use support; and some saw no statistically significant difference.”

The National Institute of Justice stated that even more research is needed to determine the value of the cameras and their most effective use when deployed. NIJ suggested that, moving forward, it would be best “to build in rigorous evaluations as law enforcement agencies expand their use of this technology.”

The latest federal data available shows that about 95% percent of major U.S. policing agencies with 500 officers or more have adopted a body camera system. The biggest suppliers of cameras and cloud storage are Axon (formerly Taser International), Motorola and Panasonic.

It’s not the cameras themselves but what the cameras yield that is the biggest moneymaker for the suppliers. This cost is a major issue that initially few in and out of law enforcement considered. Early in the development of the body cameras, some policing agencies dropped out because of the storage costs.

In time, this led to the creation of large, secure cloud-storage systems that policing agencies use, not only for storage but for sharing videos with prosecutors and defense attorneys. Initially, the storage across the country was free, but the industry moved to “monetize their interaction” with law enforcement. For the manufacturers of the camera systems, the storage of the information is their bread and butter, not the cameras, which can cost about $1,000 each.

“Everything that’s recorded on that camera, it has to be treated as evidence,” White said. “So it has to be treated like any other piece of evidence, which means it has to be stored, it has to be stored securely; and then for how long is it going to be stored?”

There is a common misconception about camera use, former San Diego prosecutor Damon Mosler said.

“They weren’t designed to necessarily collect viable evidence,” said Mosler, who is regarded as an expert in their use. That’s because the video captures the scene after the crime has occurred and before an arrest is made.

The reality, Mosler said, is that “most policing is reactive, not proactive.”

Mosler’s perspective is as a deputy district attorney for almost 30 years in San Diego County, where he ended his career with that office by coordinating the development of policies for the cameras’ use in San Diego. Now he consults for all levels of government.

“I would say the public’s perception was that we’re going to see a lot of misconduct on these videos,” he said. But that largely has not been the case.

“Unrealistic expectations,” Arizona State University’s White said, describing how some viewed the arrival of the cameras.

“Some people really expected that they were going to be the silver bullet that was going to solve, you know, a century of tension between police and minority communities, that this was going to be it and this was going to be the magic, the magic beans that are going to fix everything,” said White, who is also co-director of training and technical assistance for the U.S. Department of Justice Body-Worn Camera Policy Program.

The amount of video captured by body camera systems has grown exponentially, Mosler said. There’s not just the video shot by the police officer first on scene, but all the other videos shot by arriving units. Then there is security video captured by street cameras and retailers’ security cameras, as well as cell phone video from citizens filming police actions. Except for the City of New Orleans, no police agency reviews all the videos coming into the system.

Mosler explained that before the cameras, a police misdemeanor case would begin with a written report of five or 10 pages, possibly accompanied by some photos associated with it. But now, the written reports remain but accompanied by several hours of video.

More serious cases entrail even more videos and documentation.

It’s a “vast tsunami of digital evidence,” Mosler said. “There’s a lot of time involved, but is it all relevant or useful?”

For example, since 2014, with the inception of the San Diego Police Department’s body-worn camera program with Axon, officers have recorded more than 6 million BWC videos, according to police records.

California law stipulates that data for “non-evidentiary incidents” must be stored for 60 days. In situations where force is used, an arrest is made or a complaint filed against an officer or agency, state law requires that footage must be stored for a minimum of two years.

By the time the Oceanside Police Department adopted its current camera system in 2020, the City Council noted in its funding of the program that the department didn’t have to buy the system, but it has become “an expectation of the community” and is considered a “best practice” for law enforcement.

The agency signed a five-year agreement with Axon. Oceanside paid $1.8 million for 253 cameras, plus costs for storing the video.

In comparison, the San Diego Police Department recently signed off on a new five-year agreement with the city for $12 million for 1,950 cameras.

Contracts reviewed for this story don’t break down the costs for cameras and storage separately; both are sold as a package deal.

Escondido’s Miller said the Axon system “meets all the requirements for secure evidence through the California Justice Information System. It’s all cloud-based. It’s redundant. The system is password protected, and then it’s got multi-factor authentication.”

“Whether it’s a photograph, a video or any other digital evidence, we can see exactly who created it, when it was uploaded, who accessed it, who played it, who it was shared with, right,” Miller said. “And then it also prohibits or doesn’t allow an officer to manipulate the video; it can’t be deleted off their camera.”

Escondido has 297 cameras now for 148 sworn officers. This includes patrol, traffic and gang enforcement, who get two cameras, as the agency’s officers take their cars home and “we want them armed with a camera at all times,” Miller said.

They also provide cameras for patrol technicians and officers who transport prisoners.

The use of the AI system Truleo to review all police recordings is the next big issue in the debate over body-worn cameras.

All audio from all officers goes into the Truleo system daily for analysis and automatic transcription highlighting both bad and good interactions; police officers might be criticized or commended.

“We invested a lot of money in body cameras to improve accountability, and Truleo helps us earn a higher return on that investment for our community,” Truleo quotes Anaheim Police Chief Jorge Cisneros as saying.

There appears to be no public interest locally in the system, but that may change. Experts interviewed for this report said that Truleo or other AI systems may be slow to gain traction, but just like cameras, the interest in the upside might force acceptance of the new technology.

“While there are many technologies that can assist first responders in their goal of protecting the community, some of these are simply gimmicky products that divert funds away from providing core services,” San Diego Police Officers Association President Jared Wilson said of emerging technologies such as Truleo. “There is no technology that can replace hiring well-qualified officers and field supervisors.”

Former prosecutor Mosler said he believes there is a way to immediately streamline the efficiency and costs of body-worn camera systems across San Diego County.

“What struck me most was the lack of regional coordination and consolidation in decisions and expenditures related to BWC purchases and deployments,” he said.

Mossler suggested looking at the Integrated Law and Justice Agency of Orange County, which created a working group led by that county’s district attorney’s office and includes all police agencies, the courts and its public defender.

“I believe it serves as a model,” Mosler said. “We coordinate very well here in San Diego, but not quite at this level of cooperation and formality to ensure results.”

J.W. August is a longtime San Diego broadcast and digital journalist.

The North Coast Current and OsideNews welcome letters to the editor and longer commentaries.

(Story updated 2/29/24 at 8:05 p.m.)