By Stephen Cooper

Because I’m blessed, but also, because I’m a writer and therefore accursed with all the selfish, self-doubting sensibilities writers share, this past Memorial Day weekend I drove from Los Angeles — through green-gold, straw-yellow, and baked-red foothills dotting the California coast — to Monterey; I went, in the first instance, to write about the Ninth Annual California Roots Music and Arts Festival (and I did), but also, I went to meet a new friend for the first time — a much more experienced writer-sufferer than me — the award-winning playwright and Pacific Grove art gallery owner Steve Hauk; I wanted to talk to Hauk, to size him up in the flesh, and also, to seek his guidance on our common affliction, namely, being writers.

Now admittedly, unlike myself, who I’d describe currently — and charitably — as a “struggling” writer, by any metric it’s easy to call Hauk “successful” without brooking disagreement. But, as this piece concerns the agony more so than the ecstasy of being a writer, I’m mindful of James Baldwin’s admonition in his essay “As Much Truth as One Can Bear” that “‘[s]uccess’ is an American word which cannot conceivably, unless it is defined in an extremely severe, ironic and painful way, have any place in the vocabulary of an artist.”

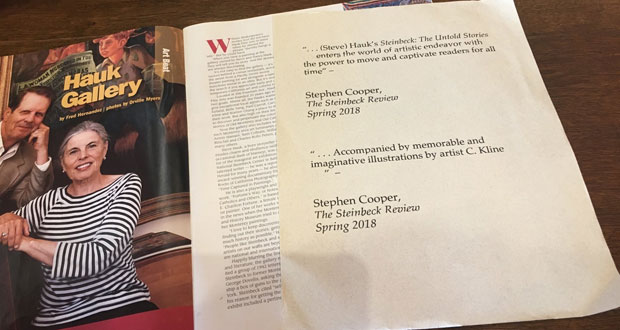

Nevertheless, and notwithstanding Baldwin’s persuasive sardonicism, I’d recently written a favorable review of Hauk’s new book, “Steinbeck: The Untold Stories” (SteinbeckNow.com 2017), in Pennsylvania State University Press’s “Steinbeck Review”; and so, as far as writers go, particularly ones whom I know personally, suffice it to say, I hold Hauk in high esteem. Given the opportunity, I knew I had to set eyes on him, to study him closer, and to see if I could discern, even if only through shaking his hand, looking into his eyes, or the osmosis of being in his presence — even if only for a short time — some bit of wisdom on how to better weather the relentlessly rocky and treacherous road of being a writer.

In a sense then, I guess I was similar to author Kurt Vonnegut’s protagonist Dwayne Hoover in “Breakfast of Champions” who endeavors to talk to “the distinguished visitors to the Arts festival” just as I “wanted to talk to [Hauk] . . . to discover if [he] had truths about life which [I] had never heard before. [Because] [h]ere is what [I] hoped new truths might do for [me]: enable [me] to laugh at [my] troubles, to go on living, and to keep out of the [mental asylum].”

Over spicy fish tacos and beer then, Hauk listened to me carefully, solicitously, and without the slightest trace of ennui, or, what would have been well-deserved reproach, as I talked, and talked, and talked, about just how “hard it is to be a writer” — dishing out one insecurity after another about what it’s like to go out on a limb, devoting oneself to writing — and art.

I talked overly long about the crappy first draft of a book I’d started writing, but regrettably, hadn’t finish; I talked about a writing class that lead to my producing several short stories, most of which were very bad, but how nonetheless they’d given me a certain sense of early confidence; I talked about how, feeding off of my former career as an attorney, I’d written scores of non-fiction columns in newspapers around the country calling for criminal justice reform, and principally, despite it seeming like a lost cause, for the abolition of the death penalty; I talked about writing about politics and about my blogs on our mutual favorite writer John Steinbeck (which, of course, Hauk already knew about and had read); and then, far too long after the last nacho remnant went cold, it occurred to me, that still, I was talking, this time telling Hauk about the reggae music stars I interview, and how, someday, I’d like to compile all these interviews into a book — and that, particularly if I don’t get the nerve to return to fiction-writing soon — it could be my first.

The more and more I talked and kvetched, the more Hauk’s eyes crinkled and the spidery lines of his wizened face softened into a smile; his expression was paternal — though not arrogant — and pensive; patiently, he sipped on his suds, waiting for my feverish, incessant, self-indulgent chatter to end. And when, finally, I shut up and leaned back from the table, ready to listen to whatever this wise and accomplished man — this writer that I admire, might say — Hauk folded his arms, and, for a long while, he was silent, saying nothing.

Watching Hauk, waiting for him to speak, my mind unconsciously flashed back to one of his “Untold [Steinbeck] Stories” called “Judith”; it’s a rollicking tale about two young artists, Judith and Elwood, who briefly cross paths with John Steinbeck. And then, for some reason I was sure, frankly, I was positive in that moment as I watched Hauk thinking, slowly opening his mouth to speak, that he was about to repeat the same advice he’d written in his story that Steinbeck had given to Judith and Elwood: to “go to Mexico ‘to learn to paint out loud.’”

Fortunately, however, despite my affinity for Mexico, that’s not what Hauk said — though he may as well have. Instead, signaling the waitress for the check, Hauk looked at me decisively, perhaps even a tad derisively, and said: “damn it man, you’re a writer; write!”

And so I will.