By Cecil Scaglione

Panicale Umbria – Umbria is perched comfortably in the shade — not the shadow, the shade– of its more renowned neighbor, Tuscany.

While the Etruscans fashioned a future that became identified as Florentine, Umbria wove its history through such hilltop towns as Assisi, Gubbio, Orvieto, Perugia, Spello and Todi, all

within an hour from this castle-cum-village plunked atop a hill midway between Rome and Florence.

— Cecil Scaglione photo

Panicale peers over undulating Tuscan hills from its perch overlooking Lake Trasimeno, the fourth largest lake on the peninsula, at the edge of the Pisa-Florence-Sienna triangle. During Hannibal’s marauding march through Italy, he ambushed and massacred some 15,000 Roman soldiers – some reports post that figure much higher – by pressing them into the lake to drown.

Hills quilted with chestnut, oak, olive and grape roll away from its shores and house dozens of villages.

Panicale also offers a peek into both medieval and modern living. Piazza Umberto I is built around the town’s 500-year-old fountain in the town’s living room.

Newlyweds have wedding photos taken here. Locals begin and end their days here. They stop gossiping only to stand up for crucifix-led funeral processions chanting the Pater Noster (Our

Father) on their way down from the massive 1,000-year-old Umbrian gothic Church of St.Michael the Archangel.

If the main piazza is the villagers’ living room, Aldo Gallo’s bar and patio is their den. It’s where they gather with hands cupped around vessels of cappuccino, espresso, wine, soda and other

liquids.

“Aldo is more important to this town than the mayor,” explained Juergen Heiss, whose first home is a nine- hour drive away in the Stuttgart area. He and his wife, Gudrun, bought an apartment

overlooking the piazza three decades ago and return to Germany during the peak-travel summertime.

They do most of their city shopping in Tuscany in Arezzo, less than an hour north of here. Sometimes they shop in the commercial hub of Umbria, Perugia, just 30 minutes away. It is the home of the Perugina chocolate factory, where visitors are greeted with trays of toothsome tantalizers and they can purchase packages of any of the company’s chocolates, candies and

cookies at factory prices.

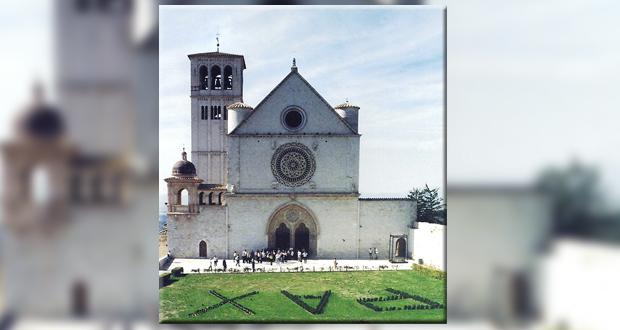

On a hillside within viewing distance from Perugia is Assisi, the birthplace of St. Francis, the founder of the religious order that established the string of 21 missions forming the backbone of

California. His remains are housed in the basilica named after him, as are those of St. Claire entombed in the church named after her at the opposite end of town.

Both churches are decorated with heart-stirring and eye-catching frescoes that are everywhere –inside and outside buildings in every community throughout the region.

A small church in Panicale (the town once had seven) houses a famous fresco — The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian. It was painted in 1505 by Piero di Cristoforo Vanucci, known as Il Perugino, whose most famous pupil was Raphael.

— Cecil Scagione photo

“There’s a funny story attached to this painting” Aldo said. On each side of this landmark Renaissance work are two small groups of bystanders, the paint on their faces long gone, watching Roman soldiers fire arrows into the martyr’s body.

“To make a fresco,” Aldo explained, “the painter puts in the colors while the plaster is still wet to preserve these works of art. The people in these groups were the patrons of the painting. Il

Perugino found out they weren’t going to finish paying him, so he painted their faces after the plaster dried. That’s why they have no faces now.”

Il Perugino was summoned by Pope Sixtus IV in 1481 to paint a portion of the Sistine Chapel. His “Charge to Peter” is still on view in the Vatican.

This artistic bent has filtered down to artisans. It’s evident everywhere but you can see it clearly just an hour away in Deruta, the ceramic capital of central Italy. It’s shops offer baked and glazed clay in all shapes, sizes, designs and colors.

Gubbio, tucked into Umbria’s northeastern corner at the foot of the Apennines, gives you a look at what medieval life looked like. People still live in 1,000-year-old houses and work in 1,000-year-old workshops. And they attend outdoor productions in a 2,000-year-old 15,000-seatRoman theater.

Getting to these hilltop villages requires a car. Taking to the road here is not the nightmare some would lead you to believe. Motorists do tailgate here, but all you have to do is get out of the way.

There are roadside pull-over areas to let motorists get by. They even give you a beep-beep “thankyou” as they pass. But you don’t have to drive to or in the big cities. Trains are best for taking you right into their hearts.

Walking four kilometers of hilly winding road to the neighboring village of Paciano for lunch faxed the terrain into our brains. It seemed to be up hill all the way there and up hill all the way

back. It did help work up an appetite And that’s another part of the fun things to experience besides the heart and history of Italy — the cuisine.

The food merits a story in itself — local pastas, regional salamis, veal, gelato, wild boar, roast rabbit, truffles, guinea fowl, fresh produce and salads, piquant olive oil, wine without additives, the list is endless.

Sheila Fitz-Hugh from Leeds, Yorkshire, a regular visitor to Umbria with her husband, Peter, said it all: “You just can’t find bad food here.”