By Cecil Scaglione

Oak Ridge TN— If you knew a half dozen decades or so ago what you are about to read, someone might have had to make you disappear.

This is where the uranium was produced for the atomic bomb that blasted open the nuclear age when it vaporized Hiroshima with the force of 14,000 tons of TNT in August 1945. Somehow, the 75,000 people who lived, worked, played and raised families in this town that erupted on the outskirts of the city of Cllinton at the rate of a new house every half hour kept their plan and purpose under security wraps.

The community was known as the Clinton Engineer Works and didn’t even show on any map before its fences and gates were torn down in 1949.

The idea was born 10 years earlier when Albert Einstein signed a letter to President Roosevelt urging him to explore military uses of uranium fission after it was discovered in Germany and the

Nazis were pursuing the production of atomic weapons.

Keeping the secret was easier then without the hordes of television and mobile-phone cameras that exist today, an octogenarian reminisced as he recalled the times. And everybody was cautioned to report on anybody talking about their work.

“Everyone just knew their job. I never knew where the uranium went or where it came from. The war was on everyone’s mind. It was like 9/11 (the 2001 terrorists’ demolition of New York’s World Trade towers) every week.”

He and his colleagues were surprised to learn of their roles in the nuclear program after the news about the Manhattan Project (the A-bomb development program) sped around the world.

After the war, the unit began to focus on separating isotopes for medical uses. Among its first advances was a cure for thyroid cancer. Other developments originating here include dental

X-ray shielding, flu vaccines, and touch-screen computer technology. Scientists here still dismantle nuclear weapons and process nuclear waste.

On the site where the world’s first nuclear reactor was built is one of the largest neutron research laboratories in the world that attracts brains from around the world to look into the

molecular structure of matter to see how things behave.

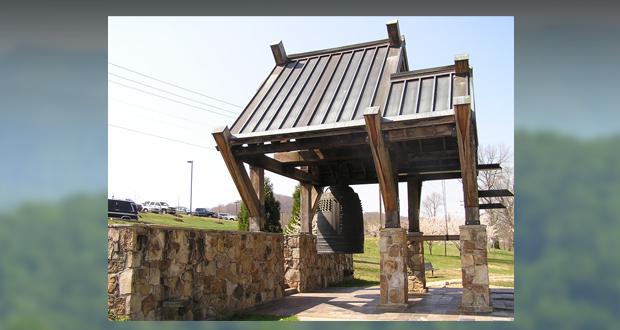

All of this, and more, is on view at the American Museum of Science and Energy, a short walk away from the International Friendship Bell that serves as a reminder of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs dropped 70 years ago.

While the Oak Ridge story embroiders the frontier of the Nuclear Age, another local story is a major but little-known chapter of the book on school desegregation.

A decade after the Oak Ridge-fed bombs helped bring an end to World War II, a dozen black students enrolled at Clinton High School to mark the beginning of the end of school segregation. This was the desegregation of the first public high school in America, one year before Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus surrounded Little Rock’s Central High with National Guardsman to bar nine black students from entering that school.

Memorials to this moment are recorded in the renovated Green McAdoo School Building just up the street from the high school. It was formerly the Clinton Colored School for grades 1 – 8 and re-opened as a museum on the 50th anniversary of the Clinton 12’s memorable walk into history.

The hills and ravines of this eastern corner of the state that stretches from the Mississippi River to the Smoky Mountains harbor historic notes as full of little surprises as the trails snaking

through the dogwoods.

For example, the first Tennessee Valley Authority dam was built on the nearby Clinch River and produced that electricity that was a major reason the Oak Ridge facility was sited here.

One other thing. The Oak Ridge Boys are not from here. They’re from Virginia, we’re told.

About Cecil Scaglione: Cecil is a former San Diego Union-Tribune writer and for a number of years has been a world traveler and writer and currently a syndicated columnist.